Amelia Earhart was adored as a very well known female aviator in the world, setting numerous aerial records, and her name being echoed through the country, being plastered on newspaper nationwide. She was an aviation pioneer of the 20s and 30s.

But then came the fateful day, 2nd July, 1937, when Amelia Earhart became famous for a very different reason, her strange and shocking disappearance. All kinds of wild theories have circulated ever since, including that she was a spy captured by the Japanese, or she did return to the U.S. and lived a double life.

While not many of these wild guesses or even research-based speculations make much sense, some theories do really hit the mark. Thanks to modern technology and the ongoing expeditions of a few dedicated individuals, who made it possible for us to make a final conclusion of this near-century long mystery.

Amelia Earhart — The Aviation Wonder Woman

From an early age, it was clear that Amelia Mary Earhart was destined for greatness. She would have been remembered as a historical icon regardless of whether or not she had disappeared.

All the mystery did was solidify her name and made it even deeper into the history books. As a youngster, growing up in Kansas, Amelia was always described as she lasts with an insatiable sense of adventure and adrenaline.

She would be climbing trees, exploring neighborhoods, and spending as much time as she could in the great outdoors, admiring the natural beauty of the world through her appetite for adventure.

The Pandemic Of 1918 Caught Amelia Earhart

Earhart, before opting career in aviation, trained as a nurse’s aide from the Red Cross. At the age of just 20, she began working voluntarily at Spadina Military Hospital. Earhart chose nursing as her career when she saw the returning wounded soldiers of World War I, while she visited her sister in Toronto.

During the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, Amelia was assigned in arduous duties as a nurse that included working late nights at the military hospital. But she soon found herself caught off the flu and suffered through pneumonia. She was then hospitalized, and eventually, she fully recovered after almost a month.

Earhart, when flying lit fire in her belly

It wasn’t until her early adult life that her radar locked onto a career in the skies. At the age of 23, Amelia strapped into a small racer plane, alongside famous flier Frank Hawks, taking off from Long Beach, California. The strong vibes for adventure finally kicked in, and she immediately decided to learn to fly.

From the various jobs that she worked for, she had a saving of around $1000, which she invested in her flying lessons and met her teacher Anita Snook, who herself was a pioneer female aviator.

It was not long enough that she was now flying an airplane seamlessly and it took only 2 years for her to break the first world record of flying to an altitude of 14,000 feet, and becoming the first female pilot to do so.

Everything seemed fine with Earhart’s career as a pilot until she started having financial issues after the investment she made into a gypsum mine failed. Further crises followed when her parents divorced and she had to sell her first bought “Canary”, a yellow Kinner Airster biplane.

She had to end her studies at MIT because her mother could no longer provide her tuition fees and other expenditures at the university. Amelia ended up finding a job first as a teacher and then as a social worker at Denison House, a Boston settlement house.

The Flight Across Atlantic

Charles Lindbergh had just completed the first solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927, creating a domino effect that would span over the following decade. Inspired by Charles’ achievements, a woman named Amy Guests intended to be the first woman to fly across the Atlantic ocean but pulled the pin at the last moment that eventually led to Amelia getting her first lucky call.

The project was sponsored by Amy, and the coordinators decided to go with Amelia Earhart, to accompany pilot Wilmer Stultz. Team of 3 including copilot and mechanic Louis Gordon departed from Trepassey Harbor, Newfoundland, and arrived at Burry Port in South Wales after flying exactly for 20 hours and 40 minutes. Although it was Stultz who did all the flying and Amelia reportedly said that she was just a “baggage on the plane, like a sack of potato”.

Fast forward to five years, on May 20th, 1932, Amelia took the critical decision to fly solo across Atlantic, ditching Wilmer and Lewis. Amelia Earhart got a Lockheed Vega airplane prepared for her award-winning flight and to become the first woman in history to fly solo and non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean.

Nobody since Lindbergh had managed to do so, and her 15-hour achievement crossing from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland to Derry in Northern Ireland was handsomely acknowledged.

Amelia Earhart was soon getting all the media attention, nationwide and was breaking records after records. For her achievements of flying solo across Atlantic, she was honored with a Distinguished Flying Cross and a Cross Of Knight of the Legion of Honor from the French Government.

Earhart was now a very well known person not only in aviation but was looked upon as an American hero throughout the nation. She also developed terms with many famous people and offices, including the First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt. But then came the mysterious incident on 2nd July, 1937, when the lady American hero, vanished without a trace.

Disappearance of Amelia Earhart

A disappearance that would evolve into one of the greatest mysteries of the 20th and 21st centuries, a mystery that has left hundreds of scientists, investigators, analysts, and aviation experts scratching their heads in bewilderment. Where did Amelia Earhart vanish? What happened to her plane?

Amelia wanted to become the first woman to fly around the world, she was passionate and dedicated to flying in the skies and was eager to achieve the next levels. After joining Purdue University as a faculty member as a counselor and a technical advisor, she planned round-the-world flight, which she didn’t know going to be proved ill-fated for her.

Earhart’s flight around the world although wasn’t the first, but it sure was the longest at 29,000 miles, as it followed a roughly tropical route. While Purdue University sponsored her expeditionary flight, Amelia got a Lockheed Electra 10E modified at Lockheed Aircraft Company, to her specifications which included modified fuselage to adjust enough fuel tanks, as the journey was going to be very long. It is believed that the plane was eventually transformed into more of a “flying gas station” with very little to no room for amenities.

The Failed Attempt And Change In Plans

Amelia’s ‘Flying Laboratory’ was now ready to take off to fly around the world with a very experienced captain accompanying her on board, Captain Harry Manning, who was going to be the navigator for Earhart’s expedition.

Manning was not just an experienced navigator but also a skilled radio operator, who also had been the captain of the SS President Roosevelt and as if that wasn’t enough he was also a skilled pilot. Earhart’s initial plan was to fly along with Manning as her navigator.

Although Amelia’s husband George P. Putnam and a Hollywood stunt pilot Paul Mantz were doubtful of Manning’s skills as a navigator, due to a previous navigation error Manning made during a flight which included Earhart, Putnam, and Manning. While Mantz was also a business partner to Earhart, running her Flying School, he was also a good friend to her who had previously helped Amelia with her flying skills.

Being a friend and advisor to Amelia, Mantz, and Putnam after testing Manning’s performance at navigation, decided to assign another navigator. Eventually, Fred Noonan was chosen as a second navigator as he was considered to be more capable of dealing with celestial navigation for aircraft, being experienced with both marine and flight navigation.

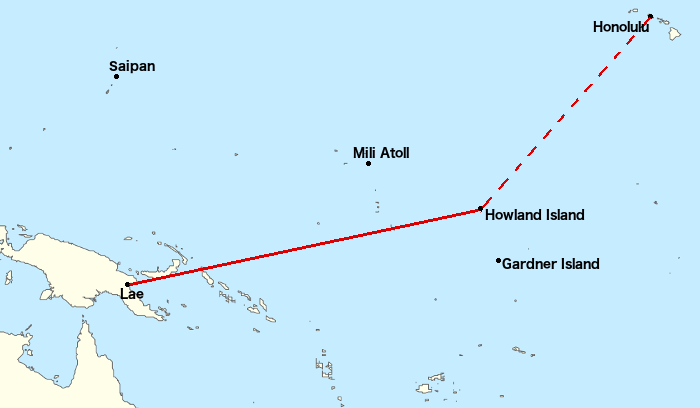

The changed plan included Noonan to accompany Earhart as her navigator from Hawaii to Howland Island, and after that Manning would be continuing with Earhart to Australia followed by her flying solo from there.

Her first attempt happened on 17th March 1937, when Earhart along with Manning, Noonan, and Mantz left Oakland, California for Honolulu, Hawaii. Mantz was being a technical advisor to Earhart. Due to some problems with the propeller of the Lockheed Electra, the aircraft needed servicing in Hawaii.

After 3 days, on March 20, 1937, the aircraft was ready and the flight was resumed, now with Noonan and Manning on board. As planned, the flight was to reach Howland Island, in the Pacific. But the flight never left the Luke Field.

During the takeoff, a crash happened, causing an uncontrollable ground loop, the plane was now skidding on the runway on its belly, damaging a portion of the runway. While the cause of the ground loop remains controversial, Mantz believed it to be a pilot error.

With the Lockheed severely damaged, the flight was called off and the aircraft was sent back to the Lockheed facilities for the repair. The whole incident led Manning to quit the expedition in the middle, leaving Earhart and Noonan, neither of whom was a skilled radio operator.

The Final Flight

After the second attempt, the take-off was successful, and Earhart with Noonan was now talking to the skies again. Although the takeoff wasn’t publicized this time, Earhart only announced her final plans publicly after reaching Miami from Oakland.

After flying for 22,000 miles out of the 29,000 miles, and numerous stops in South America, Africa, and Asia, Earhart and Noonan in their Lockheed Electra arrived at Lae, New Guinea on June 29, 1937. The next course of flight would be to cross the Pacific, covering the remaining 7,000 miles, but then came the ill-fated day.

The Distress Messages

After taking off from Lae Airfield, Earhart and Noonan headed towards their intended destination, Howland Island, where U.S. Coast Guard anchored their cutter Itasca to offer services such as communication and navigation to nearby aircraft, but mainly to guide Earhart locate the Howland Island by doing a radio direction finding in case Earhart used transmitter fitted in her plane or using the boilers to create dense smoke so that it can be seen over the horizon by Amelia Earhart. Although none of these helped Earhart to safely land at the Howland Island.

Itasca‘s radio operator received a distress signal from Earhart at around 7:58 AM (local time), but it seemed she couldn’t hear back from the radio operator, she said:

We must be on you, but cannot see you – but gas is running low. Have been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet.

The said transmission was the final loudest and the clearest signal from Earhart, indicating that their plane was in the immediate area. It was later found that the transmission devices on Itasca couldn’t tune at Lockheed’s 3105 kHz frequency, thus radio operator was under immense pressure to not able to help Earhart without proper communication established between the ship and her plane.

The operator tried sending Morse Code signals that Earhart acknowledged receiving but she was still unable to find her whereabouts.

Soon, the radio operator received another transmission from Amelia Earhart, which also found to be the last, in which she said:

We are on the line 157 337. We will repeat this message. We will repeat this on 6210 kilocycles. Wait. We are running on line north and south.

The operator concluded that Earhart and Noonan were deviated by about 5 nautical miles (10km) from their path, and he immediately signaled to fire the boilers to generate dense smoke. Apparently, Earhart was not able to see it.

The last transmission received from Earhart indicated that she and Noonan were following a line of position running North to South on 157-337 degrees.

Amelia Earhart’s Search

An immediate $4 million search was launched to uncover the bodies or the wreckage, concluding that their plane had crashed somewhere in the Pacific. The most expensive in history until that point but for decades leads were non-existent.

With no concrete evidence despite authorities’ best efforts, people started to wonder what actually happened to Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan.

It baffled many that how no evidence was found despite such extensive search was being carried out. Authorities had to legally declare Amelia and Fred deceased in 1939, in lack of any solid proof of the crash site, although it wasn’t proved that they had died either.

The first lead

It took a whole 3 years of search to find the first clue that could lead to Earhart and Noonan’s mysterious disappearance. The evidence lied on an empty remote Island, called Nikumaroro (Gardner Island).

A team from the Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme stumbled upon what seems to be human bones. This led to further insight including a woman’s shoe, still despite finding the bones, no evidence of the plane was found.

Many speculated that Amelia and Fred successfully landed somewhere on the Nikumaroror Island, only to eventually perish due to a lack of supplies and communication, and the plane swept out to sea. Discovery of the bones excited investigators, however upon analysis, they were declared to have belonging to a 5’5″ male. The fact that the island was once (40 years ago) had human population, solidify that the bones didn’t belonged neither to Earhart nor to Noonan.

Theories and Speculations

Since nothing can prove or provide any satisfactory answers to the disappearance of Earhart and Noonan, many speculations surfaced, while some being a total waste of time, some provided valid possibilities.

Nikumaroro Island Hypothesis

One week after Earhart’s disappearance, Nikumaroro Island was the center point of the search party for Earhart and Noonan. Investigators saw signs of previous habitation and the wreck of SS Norwich City, which was there since 1929.

Eric Bevington’s Photgraph of 1937

A cadet from the Navy named Eric Bevington took a photo of Nikumaroro Island during the search, which included the wreck of SS Norwich City. But it was not until 2010, that the photograph was closely looked upon. It was Jeff Glickman, an expert in image processing claiming that the photograph includes a smudged object, which looked like landing gear, probably from the wrecks of Lockheed Electra.

In August 2019, Robert Ballard, a famous ocean explorer who has found ocean wrecks including that from Titanic, believed that Bevington’s photograph might be plausible that it shows a landing gear.

Although, many mocked the photo to be a joke and not to be taken seriously in such an investigation, believing the smudge on Bevington’s photograph is nothing more than some local rocks.

The Human Skeleton

The skulls that were discovered in 1940, 3 years after the disappearance of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan, at first reported to be belonging to a 5’5″ european male, who probably might have been 45 to 55 years old, while neither Amelia nor Noonan had the height or age close to those figures.

Although the bones were misplaced in Fiji, and couldn’t be reexamined again, the analysis took a sharp turn in 2018, when Richart Jantz, an American anthropologist reanalyzed the earlier data using modern forensic techniques that were not available during 1941 analysis, concluded that Earhart’s bone measurement matched closely to the Nikumaroro bones than 99% of the samples that were analyzed.

However, the research by Jantz was questioned by many, believing it to be inaccurate in measurements, and lacked solid evidence. Moreover, a recent examination in 2019 of the skull reconstructed from the bones that were collected by Gerald Gallagher, in-charge of the Phoenix Island Settlement Scheme, concluded that the skull eventually didn’t belong to Amelia Earhart.

Other findings

Not only the bones, but there were other human belongings found on Nikumaroro Island, which was thought to be inhabited by humans for a very long time. This discovery by Gallagher included a bottle, a shoe, and a sextant box. A sextant box is an old fashioned navigation device used to measure the angular distances between two visible objects.

The discovered sextant box alarmed the authorities, believing it belonged to Noonan. The serial numbers marked on it were 3500 and 1542, but it was not until 2018 when it was found whom actually it belonged to, and apparently, it wasn’t Noonan.

The documents at National Archives and Records Administration revealed that a Brandis and Sons sextant box was used by operators on USS Bushnell, a U.S. Navy submarine that was sent to Nikumaroro for hydrographic surveys in 1937, and this was most probably the same sextant box that was found by Gallagher in 1940.

Amelia Earhart captured by Japanese forces

While the claims about this particular theory don’t make much sense, it still is taken into account due to the fact that a number of Earhart’s relatives and close ones have been convinced that the Japanese were involved in Amelia’s disappearance.

Some believe Amelia and Noonan were taken captive after they crashed on Japanese controlled Marshal Islands. An episode of Unsolved Mysteries on NBC-TV in 1990 interviewed a woman claimed to be a local from the Marshal Islands, who claimed to have witnessed the Japanese soldiers executing Earhart and Noonan.

Although this theory doesn’t make much sense on the account that Marshall Island distanced from Howland Island with approx. 800 miles, and to reach that far from her last reported position, Earhart had to change her northeast course, while she clearly reported being running low on fuel. It is highly unlikely that she would have taken such a decision.

Japanese forces theory was totally neglected until 2017, when History Channel aired a documentary named Amelia Earhart: The Lost Evidence.

The image above was proposed as a solid proof that Amelia and Noonan can be seen in it, at the time they were being captive on the Marshal Islands.

The photograph was taken from the National Archives, and the woman sitting on the dock facing the opposite side claimed to be Earhart, while the man to the left was Noonan, according to what was shown in the documentary.

The crashed Lockheed Electra was also believed to be seen on the far right side of the photo, behind the Japanese Military ship, Koshu Maru.

Although all these claims were quickly debunked and the documentary was discredited when a Japanese blogger found the actual source of the photograph, National Diet Library Digital Collection. The collection revealed that the photograph was taken in 1935, 2 years prior to Amelia and Noonan’s disappearance. And the person in the photograph was neither Noonan nor Amelia.

Additionally, the ship in the photo was Koshu and not Koshu Maru, which was seized by Japanese forces in World War I.

Although, the same ship was used during the search mission for Amelia Earhart and Noonan, by the Japanese along with Itasca, and Japanese seaplane tender, Kamoi.

Conclusion

Every theory that emerged over time either was debunked or was discarded in a lack of solid evidence. With no sign of the Lockheed Electra either, it is hard to say if the plane crashed on any of the islands, or else it would have been discovered by now.

It is highly possible that Amelia’s plane crashed after running out of fuel, and may or may not Amelia and Noonan survived for a few days. However it is believed that the plane carried enough fuel to reach Howland Island, but possibly it ran out of fuel while Amelia tried to search for the island.

The last two radio messages received from Amelia roughly had a difference of 30 minutes in-between, and the radiomen at Itasca concluded that they never left the Howland Island immediate area as the signals remained strong during this short period of time.

One of the U.S. Navy officers, Richard R. Black, who was also in charge of the Howland Island airstrip was present in the radio room on the Itasca when the incident happened. Black believed that the Lockheed Electra crashed into the sea on that day around 10 am, not very far from Howland.

Finding the Lockheed Electra in the deep sea would be like finding a needle in a haystack. Nauticos, a company owned by a former Navy submariner, specializing in deep-sea recoveries, David Jourdan carried out an extensive deep-sea search in about 1,200 square miles of area, at a position derived from the coordinates (157-337) broadcast by Earhart on the day she disappeared.

An expensive search costing $4.5 million sonar expedition, couldn’t even find anything close or relatable to that of the Electra, and the expedition just ended with a conclusion that Amelia and Noonan went deep into the water off Howland.

If this is to be believed, the Lockheed Electra probably rest as deep as 17,000 feet (5 km) in the sea, possibly with Amelia and Noonan strapped or stuck within the plane.

Although we don’t know for sure what happened that day, and probably someday the mystery will be solved. Amelia and Noonan might have disappeared leaving the greatest mystery behind, but as a Senior Curator of the National Air and Space Museum, Tom D. Crouch said: “The mystery is part of what keeps us interested. In part, we remember Amelia because she’s our favorite missing person.“

Follow Us